What is sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT)?

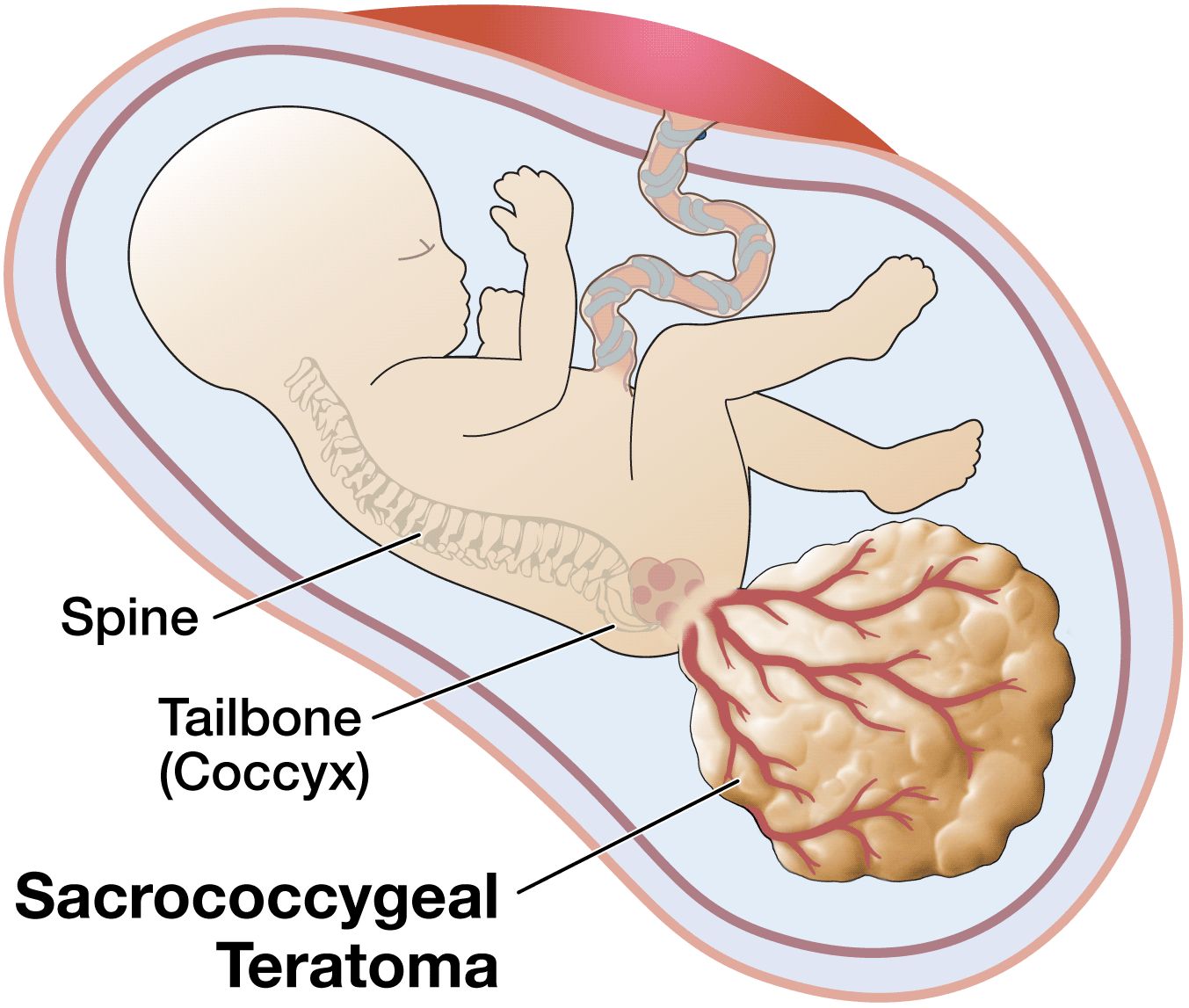

Sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is an unusual tumor that, in the newborn, is located at the base of the tailbone (coccyx). This birth defect is more common in female than in male babies. Although the tumors can grow very large, they are usually not malignant (that is, cancerous). They can usually be cured by surgery after birth, but occasionally cause trouble before birth.

SCT is usually discovered either because a blood test performed on the mother at 16 weeks shows a high alpha fetoprotein (AFP) amount, or because a sonogram is performed because the uterus is larger than it should be. The increased size of the uterus is often caused by extra amniotic fluid, called polyhydramnios. The diagnosis of SCT can be made by an ultrasound examination.

What is the outcome for a fetus with Sacrococcygeal Teratoma?

Most fetuses with sacrococcygeal teratoma do well with surgical treatment after birth. These tumors are generally not malignant. Babies with small tumors that can be removed along with the coccyx bone after birth can be expected to live normal lives. They will need to be born in a hospital with pediatric surgeons and a specialized nursery. After hospital discharge, it is our practice to follow children who have had an SCT resection closely. We recommend follow-up with a pediatric surgeon and pediatric oncologist with bloodtesting of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) throughout childhood.

Fetuses with larger tumors or tumors that go up inside the baby’s abdomen will require more complex surgery after birth, but in general do well. Again, they will have to be followed by an oncology service with blood tests for several years. Fetuses with very large tumors, which can reach the size of the fetus itself, can pose a difficult problem both before and after birth.

We have found that those SCTs that are largely cystic (fluid-filled) generally do not cause a problem for the fetus before birth. However, when the SCT is made up of mostly solid tissue, with a lot of blood flow, the fetus can suffer adverse effects. This is because the fetus’s heart has to pump not only to circulate blood to its body, but also to all the blood vessels of the tumor, which can be as big as the fetus. In essence, the heart is performing twice its normal amount of work. The amount of work the heart is doing can be measured by fetal echocardiography. This sensitive test can determine how hard the heart is working when the fetus is approaching hydrops, or heart failure. If hydrops does develop, usually in rapidly growing solid tumors, the fetus usually will not survive without immediate intervention before birth. These fetuses must be followed very closely, and may benefit from fetal surgery.

If hydrops does not develop, these babies may require Cesarean-section delivery and an extensive operation after birth. Most babies will do well once the tumor is completely removed. Long-term consequences include the recurrence of the tumor or difficulty with bowel and/or bladder control as a consequence of the surgical procedure. Your child should be followed by an oncologist and pediatric surgeon throughout childhood.

Maternal Mirror Syndrome

In cases with extreme fetal hydrops, the mother may be at risk for maternal mirror syndrome, which is a condition where the mother's condition mimics that of the sick fetus. Because of a hyperdynamic cardiovascular state, the mother develops symptoms that are similar to pre-eclampsia and may include vomiting, hypertension, peripheral edema (swelling of the hands and feet), proteinuria (protein in the urine), and pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs). Despite resection of the fetal SCT, maternal mirror syndrome may still occur.

How serious is my fetus’s Sacrococcygeal Teratoma?

In order to determine the severity of your fetus's condition it is important to gather information from a variety of tests and determine if there are any additional problems. These tests along with expert guidance are important for you to make the best decision about the proper treatment.

This includes:

- The type of defect—distinguishing it from other similar appearing problems.

- The severity of the defect—is your fetus’s defect mild or severe.

- Associated defects—is there another problem or a cluster of problems (syndrome).

The severity of sacrococcygeal teratoma is directly related to the size of the tumor and the amount of blood flow to the tumor. Both the size and the blood flow can now be accurately assessed by sonography and echocardiography. Small or medium-sized tumors without excessive blood flow will not cause a problem for the fetus. These babies should be followed with serial ultrasounds to make sure the tumor does not enlarge or the blood flow does not increase. They can be then delivered vaginally near term, and the tumor removed after birth.

Very large tumors are prone to develop excessive blood flow, which causes heart failure in the fetus. Fortunately, this is easy to detect by ultrasound. These babies need to be closely followed for the development of excess fluid in the abdomen (ascites), in the chest (pleural effusion), around the heart (pericardial effusion), or under the skin (skin edema). It is the extra blood flowing to the tumor that strains the fetal heart enough to cause heart failure(hydrops).

What are my choices during this pregnancy?

Most newborns with Sacrococcygeal Teratoma (SCT) survive and do well. Malignant tumors are unusual. Fetuses with large cystic SCTs rarely develop hydrops and therefore are not usually candidates for fetal intervention/surgery. These cases are best handled with surgical removal of the tumor after delivery. A Cesarean-section delivery of the baby may be necessary if the tumor is larger than 10 cm (4 inches).

Because all sacrococcygeal teratomas require complete surgical resection after birth, arrangements should be made for the infant to be born at a specialized hospital with pediatric surgery expertise. Fetuses with large mostly solid tumors need to be monitored frequently between 18 and 28 weeks of gestation for rapid growth of the tumor and the development of excessive blood flow and heart failure (hydrops). A small number of these fetuses with large solid tumors develop hydrops, due to extremely high blood flow through the tumor. These fetuses may be candidates for fetal intervention.

Fetal Intervention

Fetal intervention is only offered to women in whom there is evidence of heart failure in the fetus. Women who have fetuses with advanced hydrops, placentomegaly or maternal pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure, protein in the urine) are not candidates for fetal intervention as we have found that these symptoms (the so-called “mirror syndrome”) indicate an irreversible situation.

If hydrops develops after the 32nd week of pregnancy, the fetus may be delivered for intensive management after birth. Before 32 weeks gestation, fetal intervention may be advised to reverse the otherwise fatal heart failure.

Two approaches towards fetal intervention are possible for fetuses with hydrops: minimally invasive surgery and open fetal surgery. Minimally invasive fetal surgery involves inserting a needle through the mother’s abdomen and uterine wall and into the blood vessels that feed the tumor. Radiofrequency waves are used to destroy the blood vessels and, without blood flow, the tumor does not grow and heart failure (hydrops) is reversed. However, damage caused by the probe itself may be difficult to control. Another method of cutting off blood flow to the tumor is injection of drugs (for example, alcohol) that cause blood to clot. None of these methods has so far proven effective in all cases.

Open fetal surgery is an alternative option. In this case, the mother’s uterus is opened under general anesthesia and the fetus’s SCT is surgically removed. This procedure was developed at the UCSF Fetal Treatment Center, and has proven successful in a number of cases.

What will happen after birth?

All babies with Sacrococcygeal Teratoma should be delivered at a specialized hospital with pediatric surgery expertise. Tumors larger than 10 cm in diameter will require C-section delivery. The neonatologist will provide support in the intensive care nursery until the baby is stable enough for surgery. Surgical removal of small tumors is straightforward, but removal of large tumors can be very difficult and dangerous. The baby may require a blood transfusion(s) and intensive support for days or weeks after surgery. Most will get through this difficult period and enjoy a normal life. All babies should have yearly blood tests for elevated alpha feto-protein, which can signal recurrence of the tumor and possibly a malignancy. If the tumor is quite large and the surgeon performs an extensive complicated removal, there is an increased likelihood of long-term issues. A few babies may have difficulty with urination or stooling.

Support Groups & Other Resources

- March of Dimes — Researchers, volunteers, educators, outreach workers and advocates working together to give all babies a fighting chance

- Birth Defect Research for Children — a parent networking service that connects families who have children with the same birth defects

- Kids Health — doctor-approved health information about children from before birth through adolescence

- CDC - Birth Defects — Dept. of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- NIH - Office of Rare Diseases — National Inst. of Health - Office of Rare Diseases

- North American Fetal Therapy Network — NAFTNet (the North American Fetal Therapy Network) is a voluntary association of medical centers in the United States and Canada with established expertise in fetal surgery and other forms of multidisciplinary care for complex disorders of the fetus.